- News

- Investing

In conversation with Nigel Topping, the UK government’s appointed High Level Climate Change Champion.

This article is also available as a PDF download.

What is a Climate Change Champion and what does your role involve?

The role of High Level Champion was created in 2015 as part of the Paris Agreement, to help realise ambitions to lower carbon emissions and build resilience to climate change. The job is effectively recognition that countries can’t do this on their own. All sectors must play a role if we are to succeed in our goal of transforming the global economy from very high carbon to zero carbon. So, I work with all communities – private sector, local government and civil society – to drive ambition and action on climate change.

The most obvious thing that’s happened since I was appointed is that my job has been extended by a year. I took up the role in February 2020 and it was initially intended as a two-year post to cover two Conference of Parties (COP) events, which are the United Nations’ key climate change conferences. COP26 was set to take place in Glasgow in November 2020 but was inevitably postponed due to COVID-19. My role will now last for three years because of the delay and it will still cover COP27 in Africa in 2022.

This delay has given us a bit more time to get organised. I have built a team of about 50, and we work with a partnership coalition of about 200 all around the world. Our mission is to drive more ambition on achieving ‘net zero’ and figuring out the pathways to get there. Across every sector, we’ve got a good idea how to get there now, and much of the work going forward will be to improve the quality of the conversations around those pathways, as COP26 approaches.

What do you mean by net zero and what does it mean for investors?

Net zero is the global goal: to get to a net zero carbon economy. We launched a campaign we called the Race to Zero to express the urgency. Every year that we delay getting to zero will mean massive economic damage and human suffering.

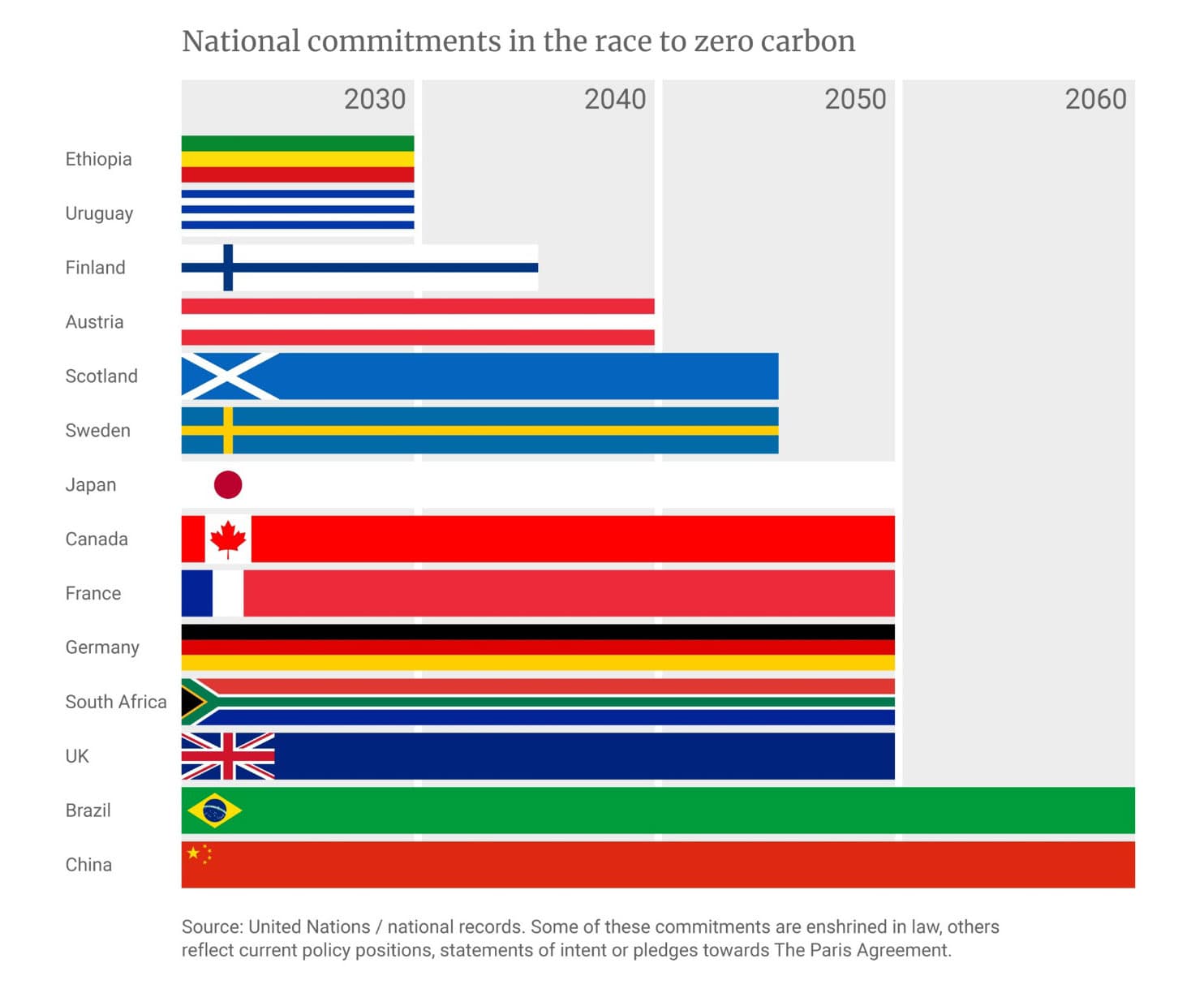

This is very quickly becoming the North Star for governments and businesses everywhere. In the last few months, we’ve had China commit to net zero before 2060, and Japan, another of the biggest economies in the world, has committed to net zero by 2050. Closer to home, the UK has a legal commitment to reach net zero by 2050 and in December, the government announced new plans aiming for an at least 68% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. Meanwhile, the EU has agreed to a 55% reduction by 2030.

So, this is the goal that everyone is aiming for. And it is important for investors because it is inevitable, and it is driving disruption in every sector of the economy. That means financial risk and financial opportunity.

We know from experience that the pace of disruptive change is exponential. By way of example, just four years ago, the International Energy Agency published forecasts that suggested we – that is, the global car buying population – would still be buying cars with combustion engines into the 2070s. Now, the expectation is that the automotive combustion engine will be a thing of the past within 10 years. Many vehicle manufacturers have been slow to electrify – many are now losing market share and it is very difficult to chase that exponential change.

The issue of climate change is a fundamental determinant of value. That is why it is important to all investors. Historically, many investors have often assumed there is a trade-off between the desire to invest in an environmentally-conscious way and the returns you could achieve – green equals diminished returns, responsible equals diminished returns. That assumption no longer applies – in fact the opposite may be true. Now, of course, green does not mean guaranteed returns, you’ve still got to invest sensibly. Not everything green is going to win – in disruption, we see a lot of failed entities. That is why a portfolio approach is sensible – even among lots of failures, the overall trend can be very powerful.

The race to zero

"Net zero is the global goal - to get to a net zero carbon economy. We launched a campaign we called the Race to Zero to express the urgency. Every year that we delay getting to zero will mean massive economic damage and human suffering."

Can you help us cut through the jargon that accompanies the climate change debate?

I would recommend that people just think about this as a zero carbon transition. Basically, we have to get carbon out of everything. The reason we say, ‘net zero’, is because we know that there are some human activities where at the moment it is hard to see a way to get them to zero carbon.

Take livestock rearing, for example. Ruminant farm animals like cows and sheep, ferment cud and burp methane, which is a powerful global warming gas. As long as we eat meat, there will be human activities that emit carbon, so we have to have a counterweight to those emissions, which is why you hear about planting trees or sequestering carbon in soil as an offset.

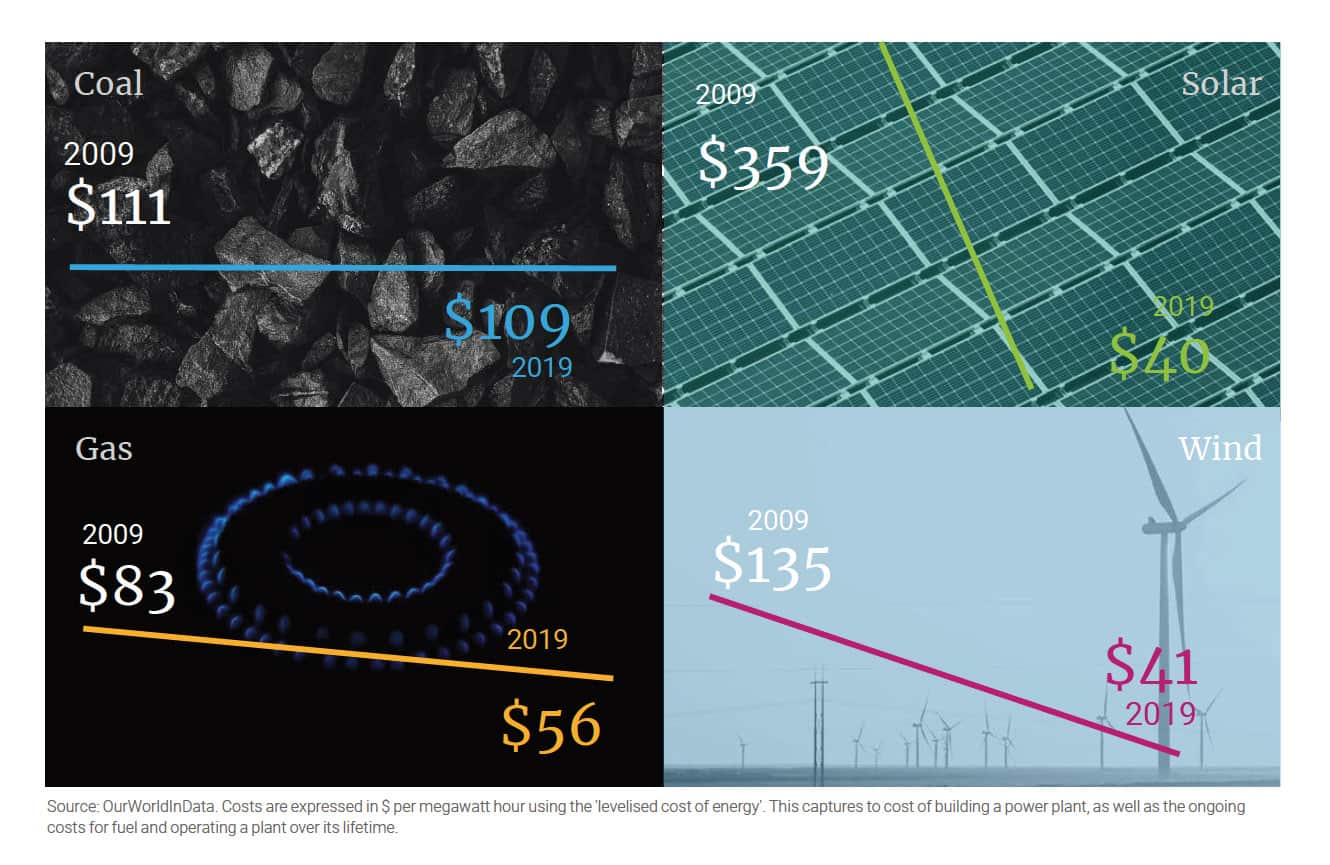

But the simplest way to think about this is that we have got to get everything to zero. That means all energy has to be non-fossil fuel. It means we have to completely decarbonise transport. The cost of renewables continues to come down in a very predictable way as volumes increase which, again, reflects the exponential nature of disruptive change.

Are there any examples of industries that are lagging behind in the transition?

Transition is a term that is used to describe the social dimension of some of the disruption. Coal mining is a classic example. Germany still has a large coal mining industry, and it has entered into a process where the government, the business community and the unions have agreed to phase out coal by 2038. This is a good example of how these transitions should be managed, to ensure that no capital or human assets become stranded. In other words, over a period of time, capital can be gradually deployed elsewhere, and jobs are created in other greener industries.

In actual fact, all experience suggests that, once there is an agreed end date, human systems and financial markets deliver that transition much faster. In the UK, the parallel would be that the government agreed to phase out all coal burning by 2025. That is still five years away, but we are pretty much there already.

The declining cost of renewable energy

"The simplest way to think about this is that we have got to get everything to zero. This means all energy has to be non-fossil fuel. The cost of renewables continues to come down in a very predictable way as volumes increase which, again, reflects the exponential nature of disruptive change."

How can the private sector do more to support the net zero commitments?

The role of the private sector is hugely important, because governments cannot move faster than they think society is ready to go. We often talk about the ambition loop. As the private sector gets more ambitious, it creates political space for politicians to be more ambitious and, of course, vice versa. I think we are seeing that as a virtuous circle right now.

The main thing that private companies can do is to actually make their own net zero commitment. There’s a huge coalition representing over $5 trillion of assets under management called the Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance, which I believe St. James's Place has already joined.

We are hearing more and more from global business leaders and from the generation moving into the business world, about the need to align business with societal value, or purpose as some might call it. Basically, business is screwed if it doesn’t make this change.

Students entering Harvard Business School, one of the most prestigious business schools in the world, are now pressing the faculty to change. They want to be taught how to launch, run and assist in the transformation of businesses to ones which they can be proud of being part of, because they know they’re playing a part in creating a better future for society. We are seeing much more recognition that businesses exist in society and that they have a responsibility to the society in which they operate. This has to be a positive thing.

How has COVID-19 impacted the climate change debate?

Obviously, the postponement of COP26 was the result of the pandemic – there simply wasn’t enough bandwidth to have contemplated putting on such an important and complex political negotiation this year. But actually, we’ve been surprised at how COVID has, in many ways, acted as an accelerator. I think this maybe because it has exposed the fragility of our system, and it has also perhaps highlighted how quickly companies and regulators can pivot if they have to.

For example, we were going to launch the Race to Zero in April but delayed it for obvious reasons. When we did launch in early June, we didn’t just have ministers and mayors turn up, we also had CEOs of major businesses like Nestlé and Rolls-Royce in attendance. These CEOs were obviously very preoccupied with the pivots that they had to make to the companies under their control – changing product lines, laying people off, restructuring balance sheets, truly once in a lifetime disruptive change for business leaders. But still they were saying, “no, we recognise that we have to do this”. And, actually, at a time when you’re pivoting, you might as well make the three or four pivots that you need to make together, rather than sequentially. They may never have a better opportunity to make some of these really big business model changes again.

Any closing thoughts?

My main piece of advice would be to embrace this as a decade of predictable disruption. Predictable in that we know the endpoint has to be zero. Of course, it’s not predictable in the exact technology and the exact rate of change. But we know it must happen.

It is therefore important to try to understand the exponential nature of industrial transformation. Cognitively, we are very badly wired to believe it, but empirically, it is the only way that industrial disruption has ever happened. Whether it’s horses to cars, or valves to transistors, analogue to digital or the rise of mobile telephony and the internet. In each of those disruptions, the change has been rapid. The world is littered with bad predictions, and with the confident few making a lot of money by actually backing the exponential change.

Where the opinions of third parties are offered, these may not necessarily reflect those of St. James's Place.

Some of the products and investment structures documented within this article will not be available to our clients in Asia. For information on the funds that are available please get in touch.

Most recent articles